At first it seems like the perfect name for an ancient temple complex. Göbekli Tepe. It rolls off the tongue like the fading echoes of a chanted ritual, repetitive and exotic.

|

| Credit |

|

| See original here |

|

| Possible reconstruction of the site, Credit |

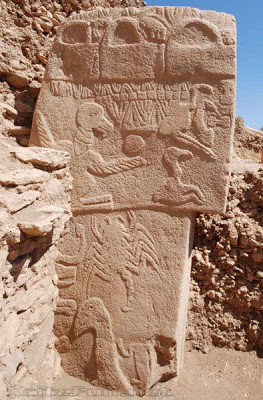

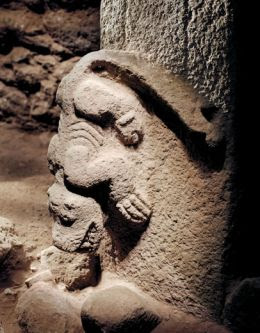

But the animals represented aren’t the prey animals you might expect from a hunter/gatherer society, rather they seem to exclusively belong to the opposite category. As Ian Hodder, a Stanford University archaeologist who excavated a nearby site explained, the carven scenes of Göbekli Tepe are “a scary fantastic world of nasty-looking beasts” including swarms of spiders, scorpions, snakes, triple-fanged monsters, and vultures.

|

| Close up of human hands on one of the pillars, implying that they represent spirits. Credit |

But even if sky burial wasn’t the purpose of this temple Schmidt argues vehemently that this was indeed a temple. “There are no traces of daily life,” he explains. “No fire pits. No trash heaps. There is no water here.”

In fact the nearest water source was about three miles away. And if there are no domestic buildings on site or any residences, then the site may well be purely a ceremonial location. The only evidence of food at all are the thousands of gazelle and aurochs bones found at there, which seems to imply that those who worked at the temple were fed by shipments of game from far-off hunts.

|

| Credit |

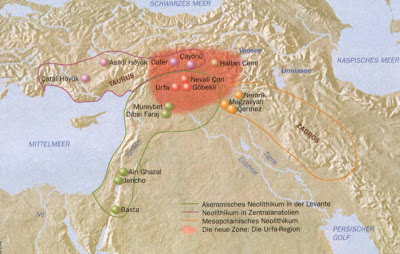

This means that this huge complex, which predates any known settlement anywhere in the entire world (as well as pottery, metallurgy, and the invention of writing or the wheel), was the first building that mankind created. If this is true then the order that we currently have things: first agriculture, then villages, then religion and government, might be turned on its head. Schmidt thinks that this location itself was the catalyst for the development of agriculture.

DNA analysis of domesticated and wild wheat seems to support his conclusion. It seems that the wild wheat with the closest DNA sequence to modern domesticated wheat grows on Mount Karaca Dağ, approximately 20 miles away from the dig site, which implies that this is where wheat was first domesticated

|

| Credit |

Strangely enough, unlike Stonehenge which remained a single stone circle for most of its existence, Göbekli Tepe’s stones were replaced and rebuilt many times. Every dozen of years or so the outer ring of pillars was filled in with dirt and another, inner ring was built inside of them. Sometimes this process was repeated once more, before the entirety of the stone circle was buried in dirt and another ring was created nearby or, sometimes, right on top of the old filled-in ring.

Were the stones believed to have lost their power? Or was there something else at play here?

Even stranger, around about 8,000 BC the complex was entombed. Not abandoned, that wouldn’t be strange, but carefully, intentionally buried by hundreds of cubic feet of soil, stones, and animal bones. It was this very burial which preserved the site so wonderfully for modern archeologists. But what happened?

|

| Credit |

It’s possible that it was a result of their discovery of agriculture. The archaeological evidence of the area shows that at the time the site was first active the surrounding area wasn’t the dry, barren desert that it is today. It was lushly green, filled with prey animals and plants.

But as the people of the area discovered farming and chopped down the surrounding trees the soil began to erode away and weaken. Eventually the soil was too depleted to support any further growth and, in the face of Dust Bowl-like conditions, the area was abandoned.

|

| Credit |

Perhaps the stones were entombed because the people of the area, having found religion, feared that they had angered the spirits. Perhaps they wished to abandon the area, but didn’t want to leave a sacred place open to the elements. Or perhaps they just wanted to give the mountain a more interesting top.

But however it happened, those people left us with a wealth of information about their lives and more mysteries to solve.